3. Riparian Conditions

Shoreline Buffer Land Cover Evaluation

The riparian or shoreline zone is that special area where the land meets the water. Well-vegetated shorelines are critically important in protecting water quality and creating healthy aquatic habitats, lakes and rivers. Natural shorelines intercept sediments and contaminants that could impact water quality conditions and harm fish habitat in streams. Well established buffers protect the banks against erosion, improve habitat for fish by shading and cooling the water and provide protection for birds and other wildlife that feed and rear young near water. A recommended target (from Environment Canada’s Guideline: How Much Habitat is Enough?) is to maintain a minimum 30 metre wide vegetated buffer along at least 75 percent of the length of both sides of rivers, creeks and streams.

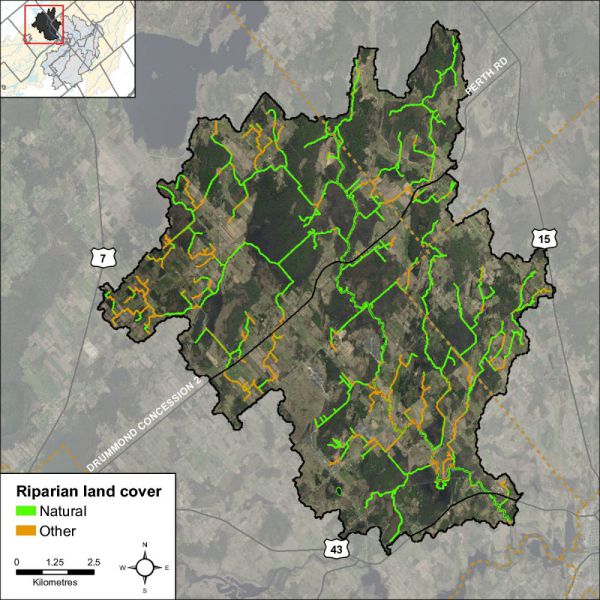

Figure 16 shows the extent of the naturally vegetated riparian zone along a 30 metre wide strip of shoreline of Black Creek and its tributaries. This information is derived from a dataset developed by the RVCA’s Land Cover Classification Program through heads-up digitization of 20cm DRAPE ortho-imagery at a 1:4000 scale, which details the catchment landscape using 10 land cover classes.

This analysis shows that the riparian buffer in the Black Creek catchment is comprised of wetland (55 percent), crop and pastureland (28 percent), woodland (12 percent), roads (three percent) and settlement areas (two percent). Additional statistics for the Black Creek catchment are presented in Table 10 and show that there has been very little change in shoreline cover from 2008 to 2014.

| Riparian Land Cover | 2008 | 2014 | Change - 2008 to 2014 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area | Area | Area | |||||||

| Ha. | Percent | Ha. | Percent | Ha. | Percent | ||||

| Wetland | 616 | 56 | 612 | 55 | -4 | -1 | |||

| > Unevaluated | (430) | (39) | (426) | (38) | (-4) | (-1) | |||

| > Evaluated | (186) | (17) | (186) | (17) | (0) | (0) | |||

| Crop & Pasture | 312 | 28 | 308 | 28 | -4 | ||||

| Woodland | 130 | 12 | 134 | 12 | 4 | ||||

| Transportation | 35 | 3 | 35 | 3 | |||||

| Settlement | 14 | 1 | 18 | 2 | 4 | 1 | |||

Black Creek Overbank Zone

Riparian Buffer Width Evaluation

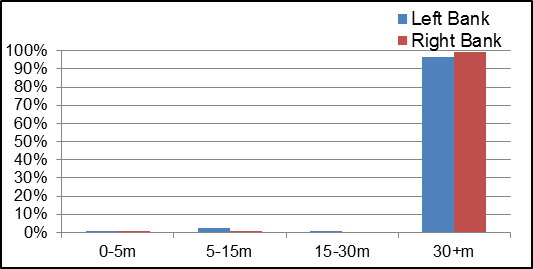

Figure 17 demonstrates the buffer conditions of the left and right banks separately. Black Creek had a buffer of greater than 30 meters along 100 percent of the right bank and 97 percent of the left bank.

Adjacent Land Use

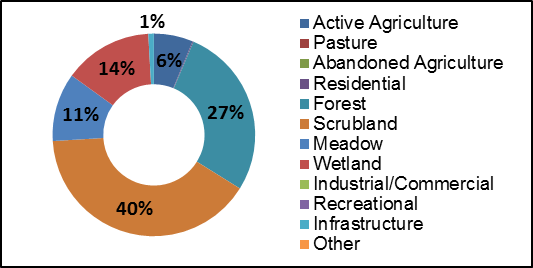

The RVCA’s Stream Characterization Program identifies eight different land uses beside Black Creek (Figure 18). Surrounding land use is considered from the beginning to end of the survey section (100m) and up to 100m on each side of the creek. Land use outside of this area is not considered for the surveys but is nonetheless part of the subwatershed and will influence the creek. Natural areas made up 92 percent of the stream, characterized by wetlands, forest, scrubland and meadow. The remaining land use consisted of active agriculture and infrastructure in the form of road crossings.

Black Creek Shoreline Zone

Instream Erosion

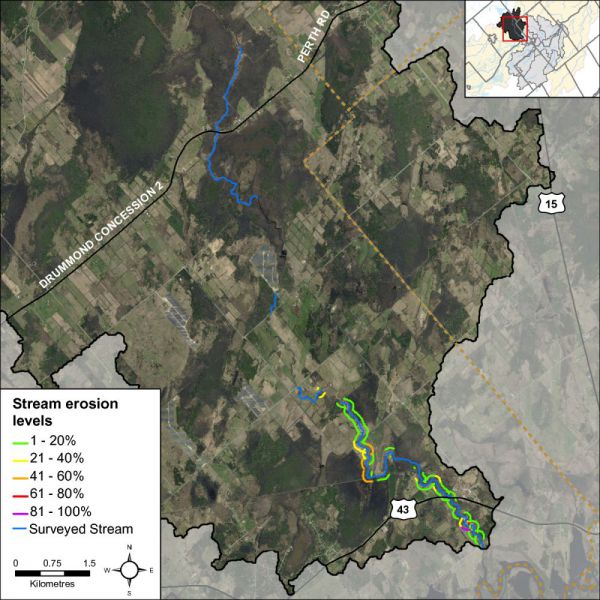

Erosion is a normal, important stream process and may not affect actual bank stability; however, excessive erosion and deposition of sediment within a stream can have a detrimental effect on important fish and wildlife habitat. Poor bank stability can greatly contribute to the amount of sediment carried in a waterbody as well as loss of bank vegetation due to bank failure, resulting in trees falling into the stream and the potential to impact instream migration. Figure 19 shows low to moderate levels of erosion observed along Black Creek.

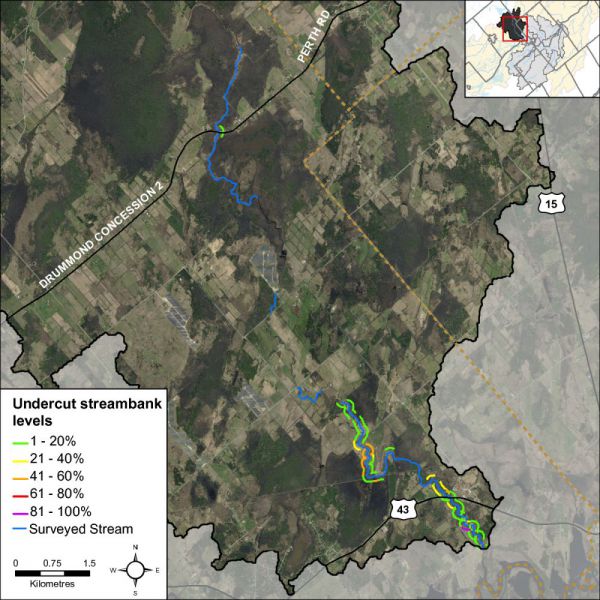

Undercut Stream Banks

Undercut banks are a normal and natural part of stream function and can provide excellent refuge areas for fish. Figure 20 shows that Black Creek had low to moderate levels of undercut banks.

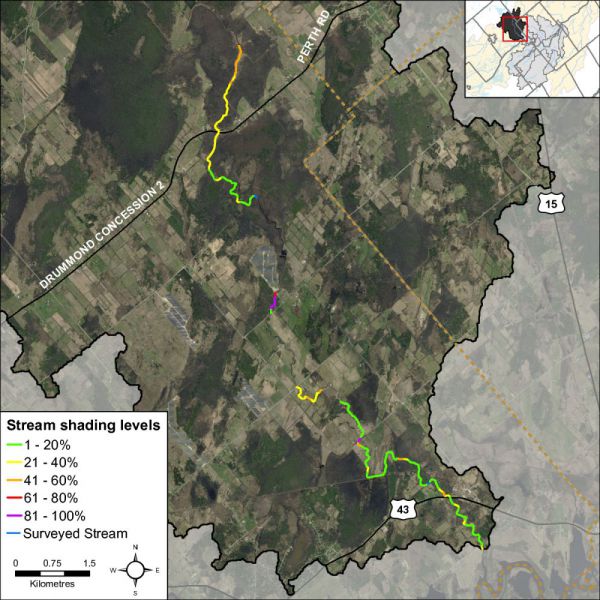

Stream Shading

Grasses, shrubs and trees all contribute towards shading a stream. Shade is important in moderating stream temperature, contributing to food supply and helping with nutrient reduction within a stream. Figure 21 shows variable stream shading conditions ranging from low levels to high levels along Black Creek.

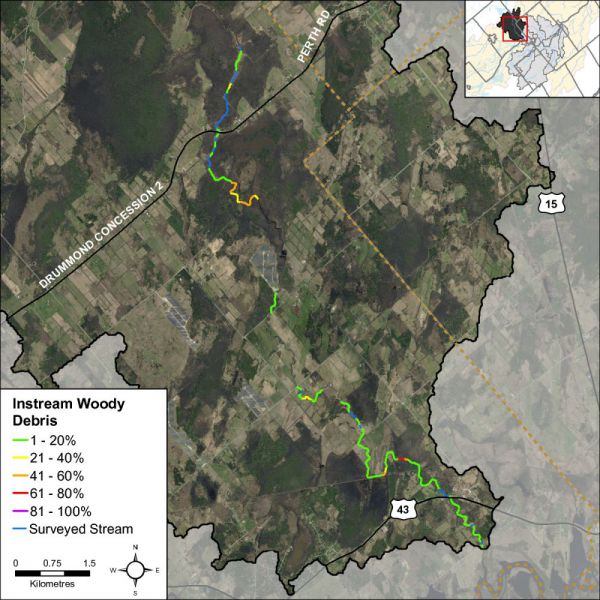

Instream Woody Debris

Figure 22 shows that the majority of Black Creek had low to moderate levels of instream woody debris in the form of branches and trees. Instream woody debris is important for fish and benthic invertebrate habitat, by providing refuge and feeding areas.

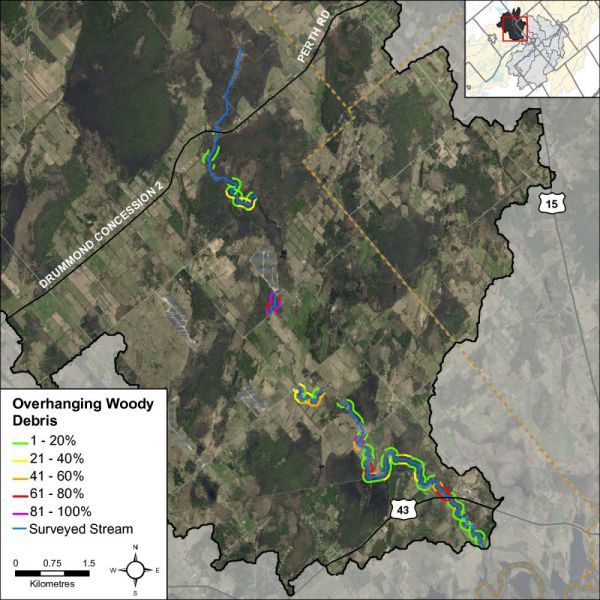

Overhanging Trees and Branches

Figure 23 shows low to high levels of overhanging branches and trees along Black Creek. Overhanging branches and trees provide a food source, nutrients and shade which helps to moderate instream water temperatures.

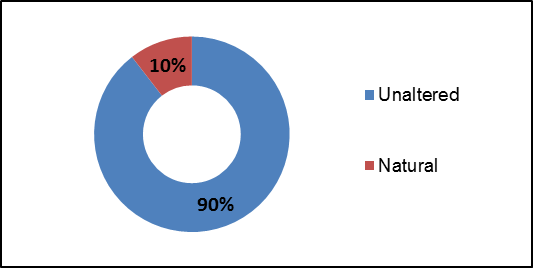

Anthropogenic Alterations

Figure 24 shows 90 percent of Black Creek remains “unaltered” with no anthropogenic alterations. Ten percent of Black Creek was classified as natural with minor anthropogenic changes in the form of road crossings.

Black Creek Instream Aquatic Habitat

Benthic Invertebrates

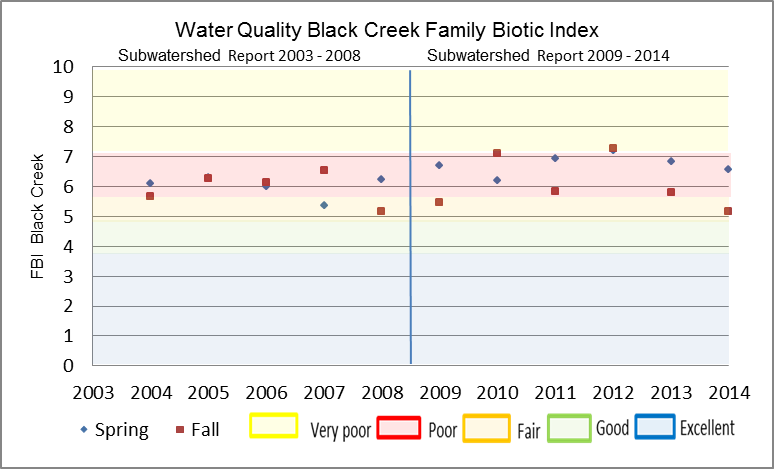

Freshwater benthic invertebrates are animals without backbones that live on the stream bottom and include crustaceans such as crayfish, molluscs and immature forms of aquatic insects. Benthos represent an extremely diverse group of aquatic animals and exhibit wide ranges of responses to stressors such as organic pollutants, sediments and toxicants, which allows scientists to use them as bioindicators. As part of the Ontario Benthic Biomonitoring Network (OBBN), the RVCA has been collecting benthic invertebrates at the Poonamalie Road site on Black Creek since 2003. Monitoring data is analyzed for each sample site and the results are presented using the Family Biotic Index, Family Richness and percent Ephemeroptera, Plecoptera and Trichoptera.

The Hilsenhoff Family Biotic Index (FBI) is an indicator of organic and nutrient pollution and provides an estimate of water quality conditions for each site using established pollution tolerance values for benthic invertebrates. FBI results for Black Creek are separated by reporting period 2003 to 2008 and 2009 to 2014. “Poor” to “Fair” water quality conditions being observed at the Black Creek sample location for the period from 2003 to 2014 (Fig.25) using a grading scheme developed by Conservation Authorities in Ontario for benthic invertebrates.

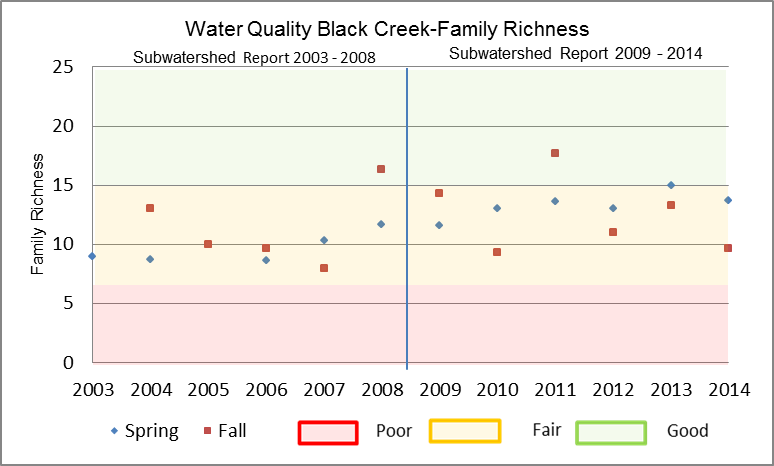

Family Richness measures the health of the community through its diversity and increases with increasing habitat diversity suitability and healthy water quality conditions. Family Richness is equivalent to the total number of benthic invertebrate families found within a sample. Black Creek is reported to have “Fair” to “Good” family richness (Fig.26).

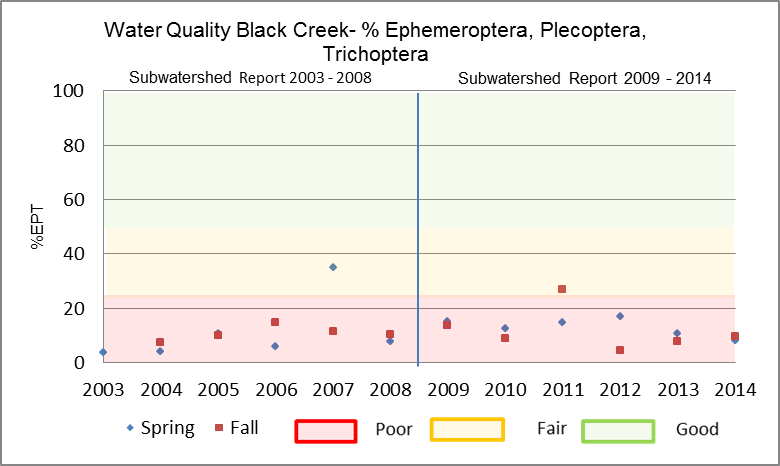

Ephemeroptera (Mayflies), Plecoptera (Stoneflies), and Trichoptera (Caddisflies) are species considered to be very sensitive to poor water quality conditions. High abundance of these organisms is generally an indication of good water quality conditions at a sample location. The community structure is dominated by species that are not sensitive to poor water quality conditions. As a result, the EPT indicates that Black Creek is reported to have “Poor” to “Fair” water quality (Fig.27) from 2003 to 2014.

Conclusion

Overall Black Creek aquatic habitat conditions from a benthic invertebrate perspective range from “Poor” to "Fair" from 2003 to 2014.

Habitat Complexity

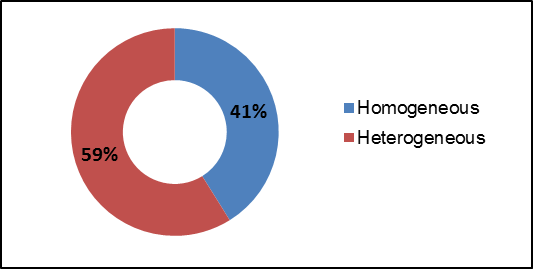

Streams are naturally meandering systems and move over time; there are varying degrees of habitat complexity, depending on the creek. Examples of habitat complexity include variable habitat types such as pools and riffles as well as substrate variability and woody debris structure. A high percentage of habitat complexity (heterogeneity) typically increases the biodiversity of aquatic organisms within a system. Fifty nine percent of Black Creek was considered heterogeneous, as shown in Figure 28.

Instream Substrate

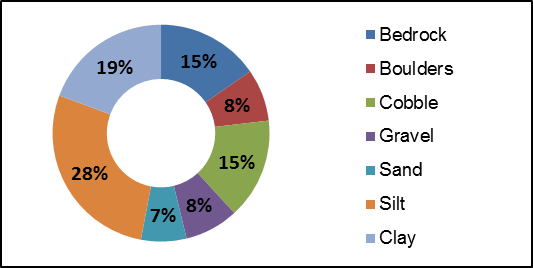

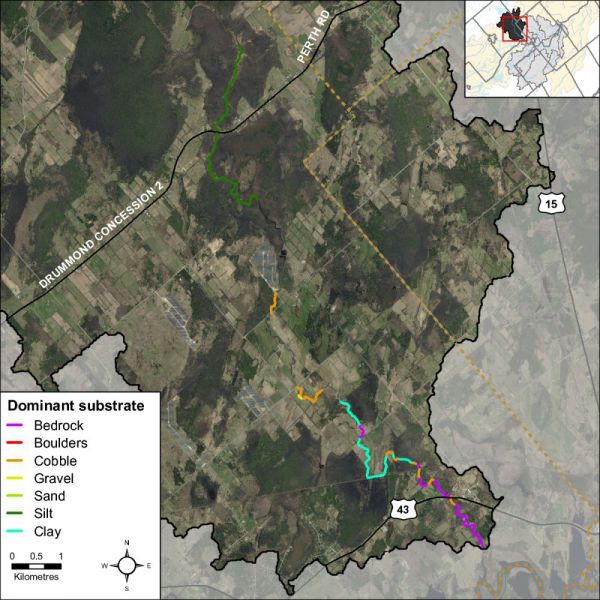

Diverse substrate is important for fish and benthic invertebrate habitat because some species have specific substrate requirements and for example will only reproduce on certain types of substrate. Figure 29 shows that 28 percent of the substrate observed on Black Creek was dominated by cobble. Overall substrate conditions were highly variable along Black Creek. Figure 30 shows the dominant substrate type observed for each section surveyed along Black Creek.

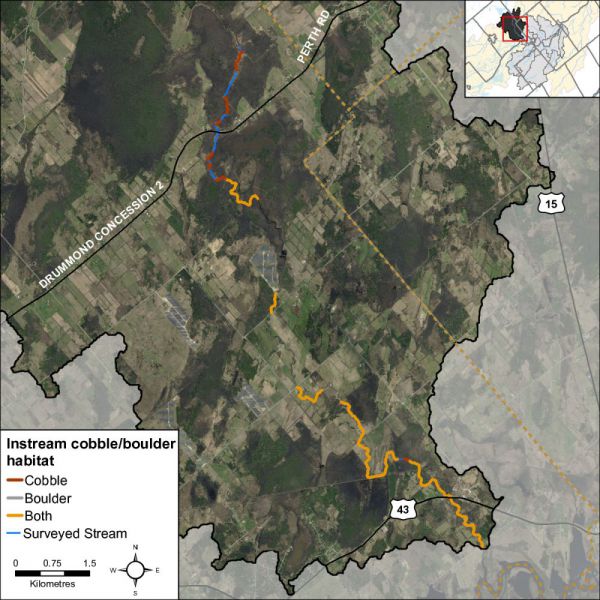

Cobble and Boulder Habitat

Boulders create instream cover and back eddies for large fish to hide and/or rest out of the current. Cobble provides important spawning habitat for certain fish species like walleye and various shiner species who are an important food source for larger fish. Cobble can also provide habitat conditions for benthic invertebrates that are a key food source for many fish and wildlife species. Figure 31 shows where cobble and boulder substrate are found in Black Creek.

Instream Morphology

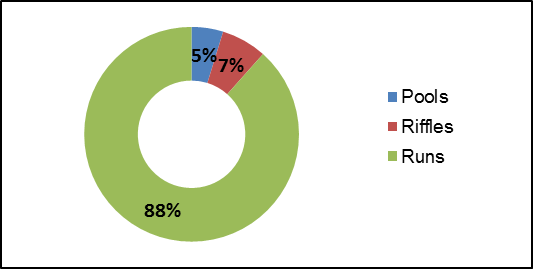

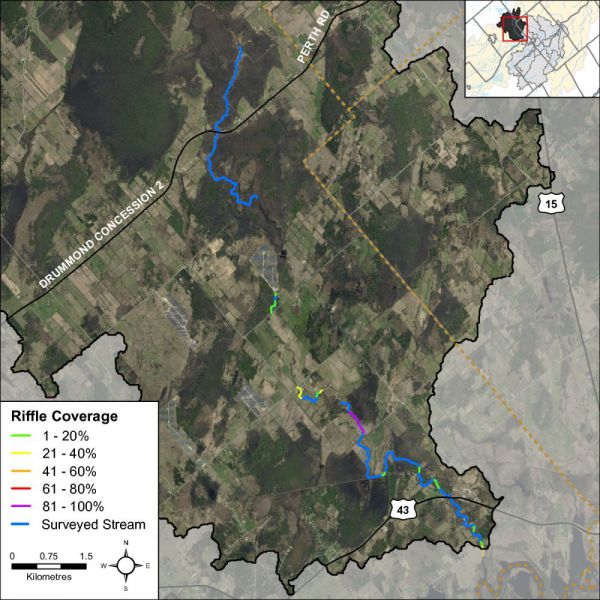

Pools and riffles are important habitat features for fish. Riffles are areas of agitated water and they contribute higher dissolved oxygen to the stream and act as spawning substrate for some species of fish, such as walleye. Pools provide shelter for fish and can be refuge pools in the summer if water levels drop and water temperature in the creek increases. Pools also provide important over wintering areas for fish. Runs are usually moderately shallow, with unagitated surfaces of water and areas where the thalweg (deepest part of the channel) is in the center of the channel. Figure 32 shows that Black Creek is fairly uniform; 88 percent consists of runs, 7 percent riffles and 5 percent pools. Figure 33 shows where riffle habitat was observed along Black Creek.

Vegetation Type

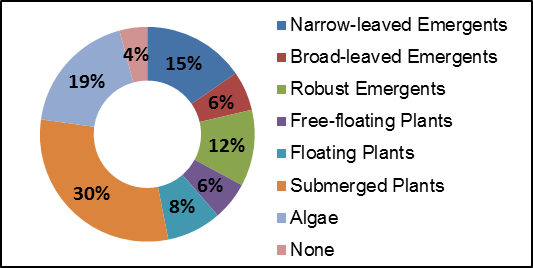

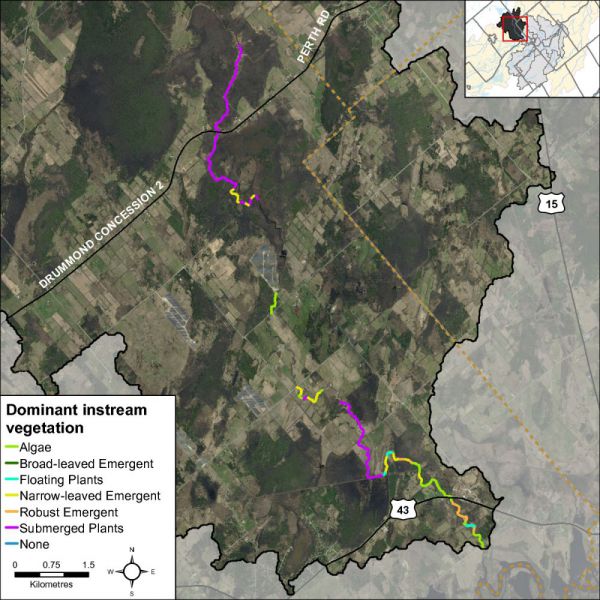

Instream vegetation provides a variety of functions and is a critical component of the aquatic ecosystem. For example emergent plants along the shoreline can provide shoreline protection from wave action and important rearing habitat for species of waterfowl. Submerged plants provide habitat for fish to find shelter from predator fish while they feed. Floating plants such as water lilies shade the water and can keep temperatures cool while reducing algae growth. The dominant vegetation type recorded at thirty percent consisted of submerged plants. Black Creek had high levels of diversity for instream vegetation. Figure 34 depicts the plant community structure for Black Creek. Figure 35 shows the dominant vegetation type observed for each section surveyed along Black Creek.

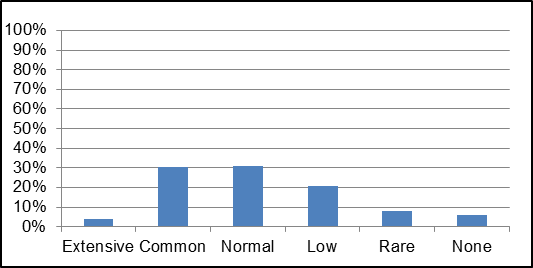

Instream Vegetation Abundance

Instream vegetation is an important factor for a healthy stream ecosystem. Vegetation helps to remove contaminants from the water, contributes oxygen to the stream, and provides habitat for fish and wildlife. Too much vegetation can also be detrimental. Figure 36 demonstrates that Black Creek had sections dominated by common and normal low levels of instream vegetation for fifty two percent of its length.

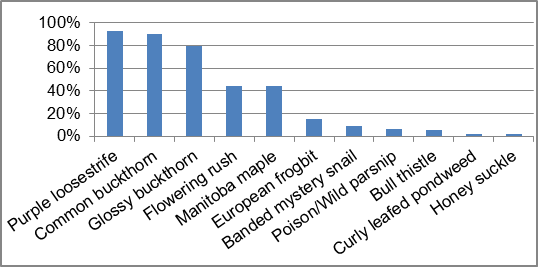

Invasive Species

Invasive species can have major implications on streams and species diversity. Invasive species are one of the largest threats to ecosystems throughout Ontario and can out compete native species, having negative effects on local wildlife, fish and plant populations. One hundred percent of the sections surveyed along Black Creek had invasive species (Figure 37). The invasive species observed in Black Creek were European frogbit, purple loosestrife, glossy and common buckthorn, banded mystery snail, curly leafed pondweed, flowering rush, bull thistle, honey suckle, wild parsnip and Manitoba maple. Figure 38 shows the frequency of the invasive species observed along Black Creek.

Black Creek Water Chemistry

During the stream characterization survey, a YSI probe is used to collect water chemistry information. Dissolved oxygen, conductivity and pH are measured at the start and end of each section.

Dissolved Oxygen

Dissolved oxygen is a measure of the amount of oxygen dissolved in water. The Canadian Environmental Quality Guidelines of the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment (CCME) suggest that for the protection of aquatic life the lowest acceptable dissolved oxygen concentration should be 6 mg/L for warmwater biota and 9.5 mg/L for coldwater biota (CCME, 1999). Figure 39 shows that the dissolved oxygen in Black Creek was within the threshold for warmwater biota in most reaches of the system, however areas in the headwaters were below the warmwater threshold. The average dissolved oxygen levels observed within the main stem of Black Creek was 6.02mg/L which is within the recommended levels for warmwater biota.

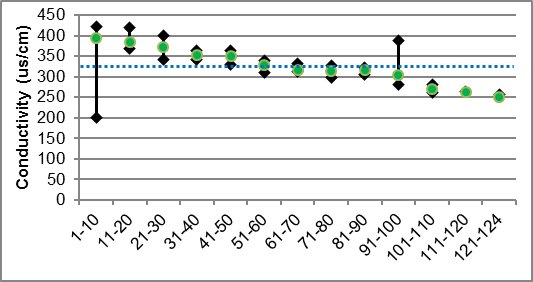

Conductivity

Conductivity in streams is primarily influenced by the geology of the surrounding environment, but can vary drastically as a function of surface water runoff. Currently there are no CCME guideline standards for stream conductivity, however readings which are outside the normal range observed within the system are often an indication of unmitigated discharge and/or stormwater input. The average conductivity observed within the main stem of Black Creek was 328 µs/cm. Figure 40 shows that the conductivity readings for Black Creek.

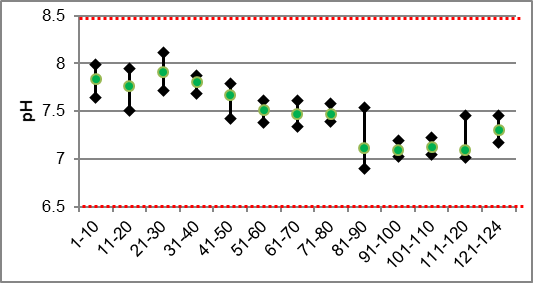

pH

Based on the PWQO for pH, a range of 6.5 to 8.5 should be maintained for the protection of aquatic life. Average pH values for Black Creek averaged 7.5 thereby meeting the provincial standard (Figure 41).

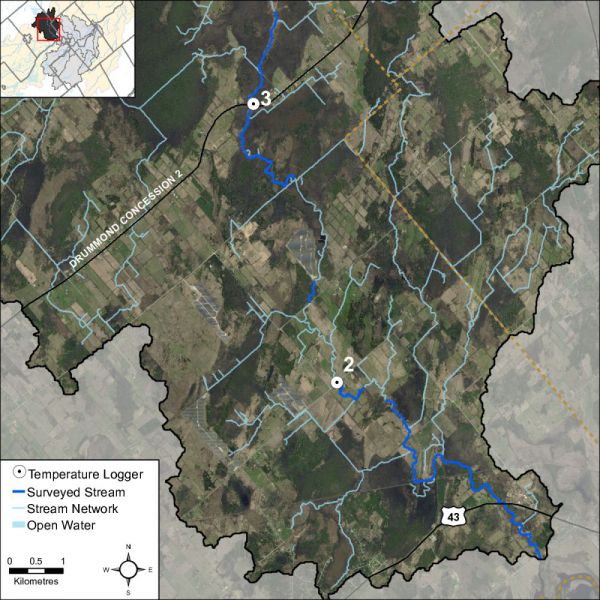

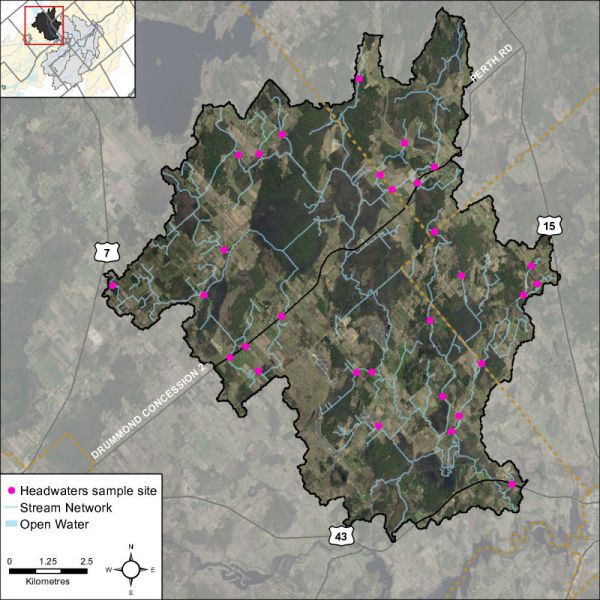

Thermal Regime

Many factors can influence fluctuations in stream temperature, including springs, tributaries, precipitation runoff, discharge pipes and stream shading from riparian vegetation. Water temperature is used along with the maximum air temperature (using the Stoneman and Jones method) to classify a watercourse as either warm water, cool water or cold water. Analysis of the data collected indicates that Black Creek is classified as a cool - warm water system with warm water reaches. Figure 42 shows the thermal sampling locations.

| SITE ID | Y_WATER | X_AIR | CLASSIFICATION | PROGRAM | YEAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BC2 - Armstrong Rd | 23.8 | 28.4 | COOL-WARM | MACRO | 2014 |

| BC3 - Drummond Concession Rd 2 | 26.2 | 28.5 | WARMWATER | MACRO | 2014 |

Each point on the graph represents a temperature that meets the following criteria:

- Sampling dates between July 1st and September 7th

- Sampling date is preceded by two consecutive days above 24.5 °C, with no rain

- Water temperatures are collected at 4pm

- Air temperature is recorded as the max temperature for that day

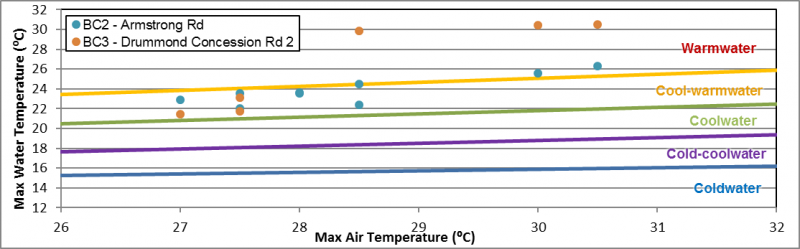

Groundwater

Groundwater discharge areas can influence stream temperature, contribute nutrients, and provide important stream habitat for fish and other biota. During stream surveys, indicators of groundwater discharge are noted when observed. Indicators include: springs/seeps, watercress, iron staining, significant temperature change and rainbow mineral film. Figure 44 shows areas where one or more of the above groundwater indicators were observed during stream surveys and headwater assessments.

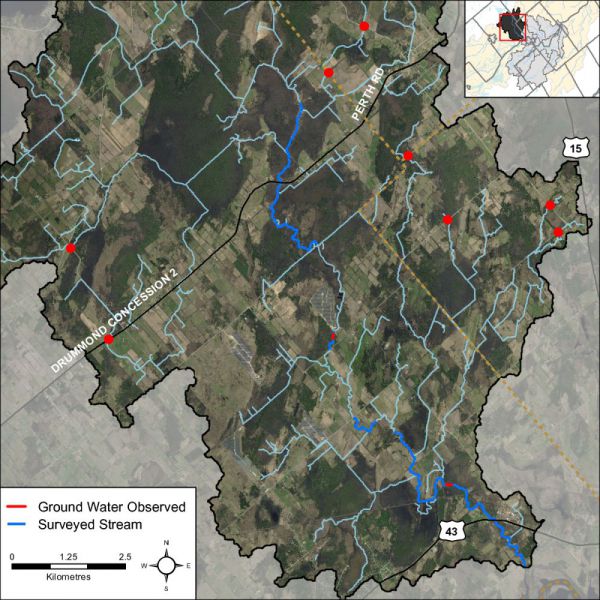

Headwaters Drainage Features Assessment

The RVCA Stream Characterization program assessed Headwater Drainage Features for the Middle Rideau subwatershed in 2014. This protocol measures zero, first and second order headwater drainage features (HDF). It is a rapid assessment method characterizing the amount of water, sediment transport, and storage capacity within headwater drainage features (HDF). RVCA is working with other Conservation Authorities and the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry to implement the protocol with the goal of providing standard datasets to support science development and monitoring of headwater drainage features. An HDF is a depression in the land that conveys surface flow. Additionally, this module provides a means of characterizing the connectivity, form and unique features associated with each HDF (OSAP Protocol, 2013). In 2014 the program sampled 30 sites at road crossings in the Black Creek catchment area (Figure 45).

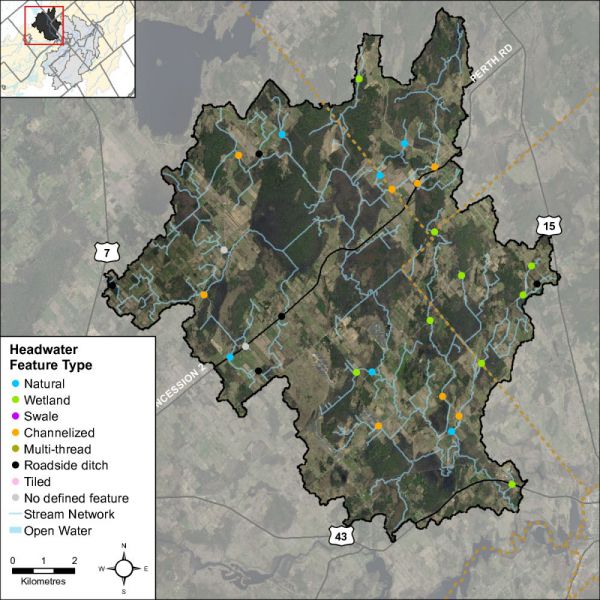

Feature Type

The headwater sampling protocol assesses the feature type in order to understand the function of each feature. The evaluation includes the following classifications: defined natural channel, channelized or constrained, multi-thread, no defined feature, tiled, wetland, swale, roadside ditch and pond outlet. By assessing the values associated with the headwater drainage features in the catchment area we can understand the ecosystem services that they provide to the watershed in the form of hydrology, sediment transport, and aquatic and terrestrial functions. The Black Creek catchment is dominated by natural channel and wetland headwater drainage features. However, there were several features classified as channelized, while there were three features that ran along the road. Two features were classified as not having a defined channel. Figure 46 shows the feature type of the primary feature at the sampling locations.

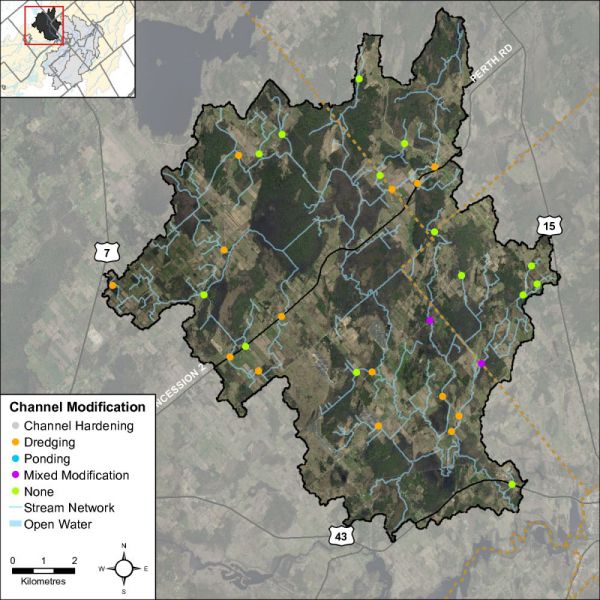

Feature Channel Modifications

Channel modifications were assessed at each headwater drainage feature sampling location. Modifications include channelization, dredging, hardening and realignments. The sampling locations for the Black Creek catchment were classified with a variety of channel modifications. Many of the features had no channel modifications, however several were classified as having mixed modifications or had been recently dredged/cleaned out. Figure 47 shows the channel modifications observed at the sampling locations for Black Creek.

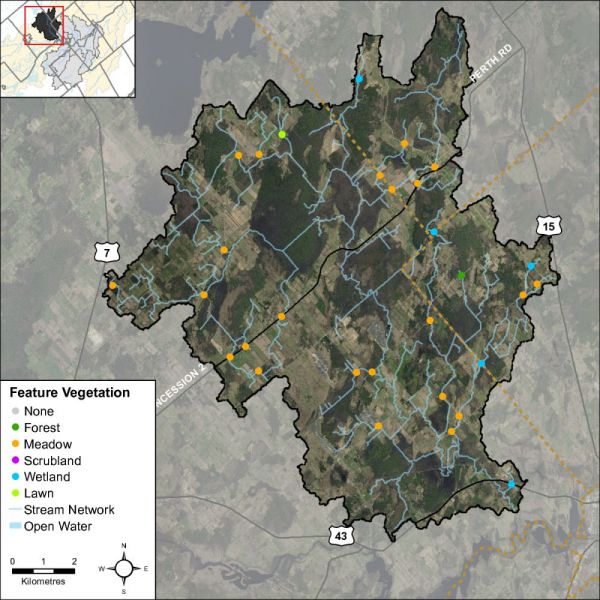

Headwater Feature Vegetation

Headwater feature vegetation evaluates the type of vegetation that is found within the drainage feature. The type of vegetated within the channel influences the aquatic and terrestrial ecosystem values that the feature provides. For some types of headwater features the vegetation within the feature plays a very important role in flow and sediment movement and provides wildlife habitat. The following classifications are evaluated no vegetation, lawn, wetland, meadow, scrubland and forest. Figure 48 depicts the dominant vegetation observed at the sampled headwater sites in the Black Creek catchment.

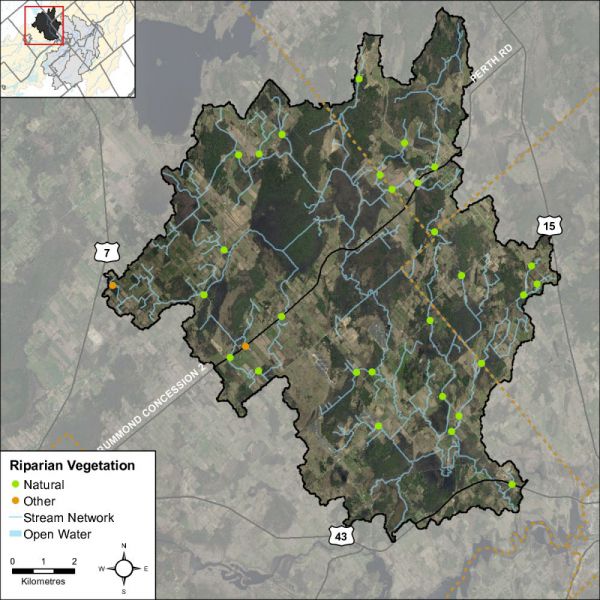

Headwater Feature Riparian Vegetation

Headwater riparian vegetation evaluates the type of vegetation that is found along the adjacent lands of a headwater drainage feature. The type of vegetation within the riparian corridor influences the aquatic and terrestrial ecosystem values that the feature provides to the watershed. The majority of the sample locations in Black Creek were dominated by natural vegetation in the form of scrubland, forest and wetland vegetation. Figure 49 depicts the type of riparian vegetation observed at the sampled headwater sites in the Black Creek catchment.

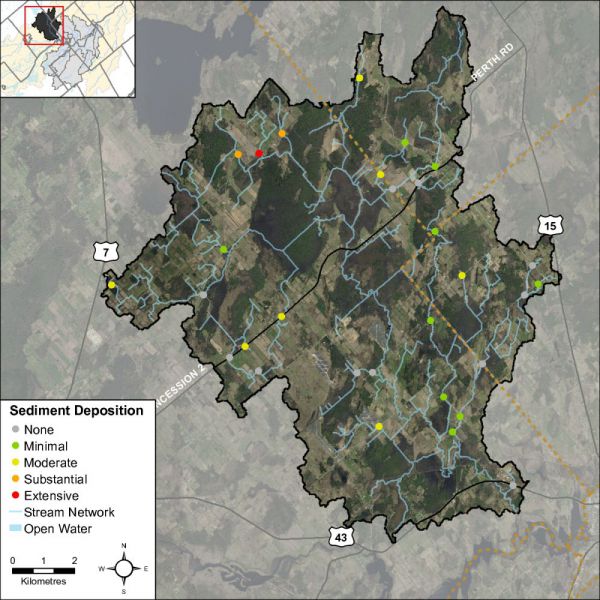

Headwater Feature Sediment Deposition

Assessing the amount of recent sediment deposited in a channel provides an index of the degree to which the feature could be transporting sediment to downstream reaches (OSAP, 2013). Evidence of excessive sediment deposition might indicate the requirement to follow up with more detailed targeted assessments upstream of the site location to identify potential best management practices to be implemented. Conditions ranged from no deposition observed to a site with substantial deposition recorded. Overall most sites had minimal to moderate levels of sediment deposition. Figure 50 depicts the degree of sediment deposition observed at the sampled headwater sites in the Black Creek catchment.

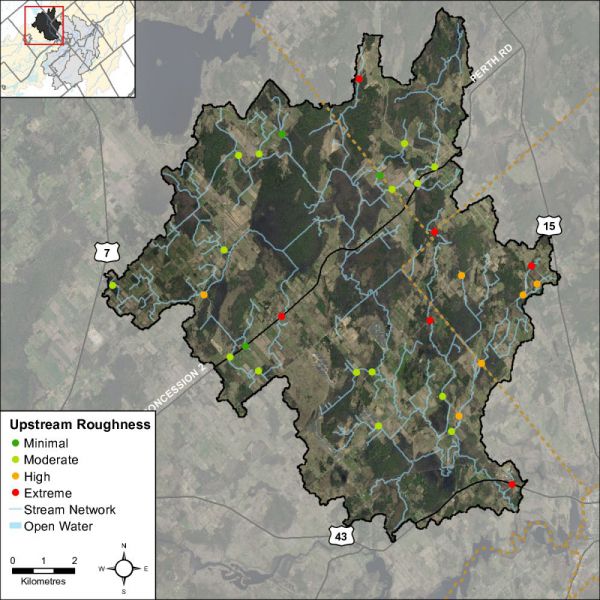

Headwater Feature Upstream Roughness

Feature roughness will provide a measure of the amount of materials within the bankfull channel that could slow down the velocity of water flowing within the headwater feature (OSAP, 2013). Materials on the channel bottom that provide roughness include vegetation, woody debris and boulders/cobble substrates. Roughness can provide benefits in mitigating downstream erosion on the headwater drainage feature and the receiving watercourse by reducing velocities. Roughness also provides important habitat conditions to aquatic organisms. Many of the sample locations in the Black Creek catchment area had extreme to moderate levels of feature roughness. Figure 51 shows the feature roughness conditions at the sampling locations in the Black Creek catchment.

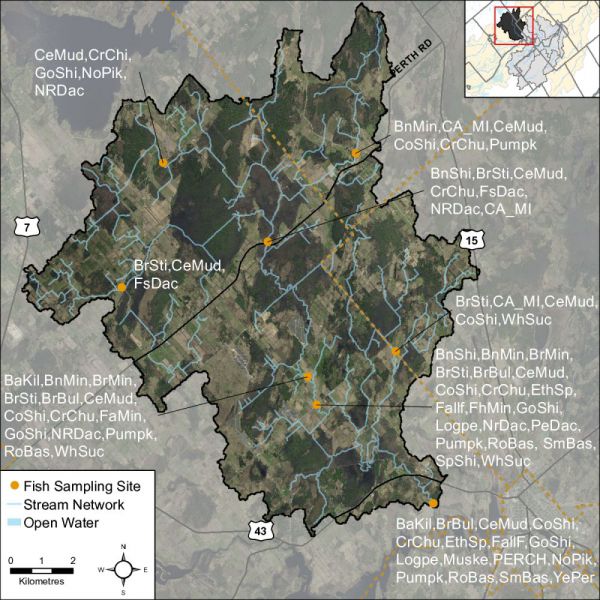

Fish Community

The Black Creek catchment is classified as a mixed community of warm and cool water recreational and baitfish fishery with 26 species observed. Table 11 lists the species observed in the catchment (Source: MNR/RVCA). Figure 52 shows the fish sampling locations for Black Creek.

| Fish Species | Fish code | Fish Species | Fish code | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| banded killifish | BaKil | fathead minnow | FhMin | ||||||

| black crappie | BlCra | finescale dace | FsDac | ||||||

| blacknose dace | BnDac | golden shiner | GoShi | ||||||

| blacknose shiner | BnShi | logperch | Logpe | ||||||

| bluegill | Blueg | northern pearl dace | PeDac | ||||||

| bluntnose minnow | BnMin | northern pike | NoPik | ||||||

| brassy minnow | BrMin | northern redbelly dace | NRDac | ||||||

| brook stickleback | BrSti | perch and darter family | PERCH | ||||||

| brown bullhead | BrBul | pumpkinseed | Pumpk | ||||||

| carps and minnows | CA_MI | rock bass | RoBas | ||||||

| central mudminnow | CeMud | smallmouth bass | SmBas | ||||||

| common shiner | CoShi | spotfin shiner | SpShi | ||||||

| creek chub | CrChu | white sucker | WhSuc | ||||||

| etheostoma sp. | Ethsp | yellow perch | YePer | ||||||

| fallfish | Fallf |

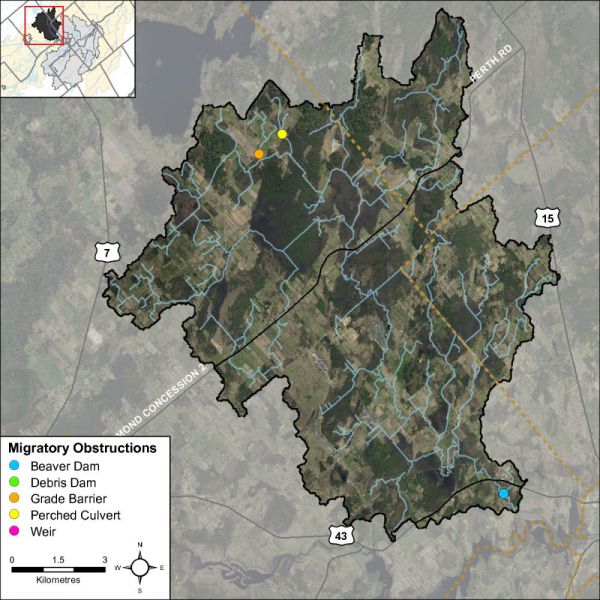

Migratory Obstructions

It is important to know locations of migratory obstructions because these can prevent fish from accessing important spawning and rearing habitat. Migratory obstructions can be natural or manmade, and they can be permanent or seasonal. Figure 53 shows that the headwaters and the main stem of Black Creek had a beaver dam, perched culvert and a grade barrier at the time of the survey in 2014.

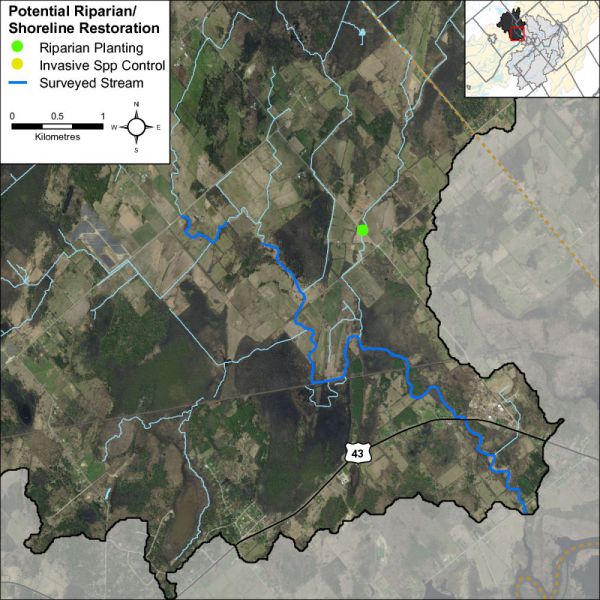

Riparian Restoration

Figure 54 depicts the locations where various riparian restoration activities can be implemented as a result of observations made during the stream survey and headwater drainage feature assessments. The surveys identified one riparian planting opportunity on a headwater feature.