4.0 Port Elmsley Catchment: Land Cover

Land cover and any change in coverage that has occurred over a six year period is summarized for the Port Elmsley catchment using spatially continuous vector data representing the catchment during the spring of 2008 and 2014. This dataset was developed by the RVCA through heads-up digitization of 20cm DRAPE ortho-imagery at a 1:4000 scale and details the surrounding landscape using 10 land cover classes.

4.1 Port Elmsley Catchment Land Cover/Change

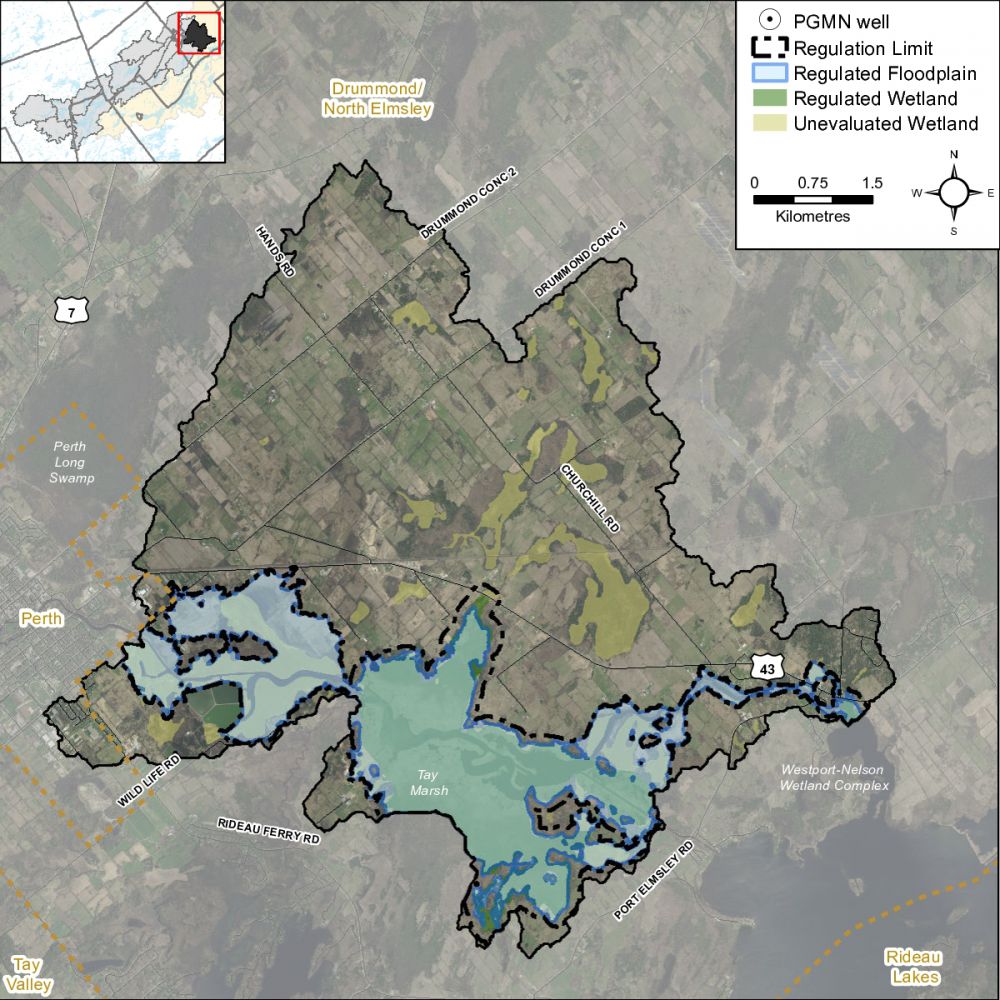

As shown in Table 7 and Figure 1, the dominant land cover type in 2014 is crop and pastureland.

| Land Cover | 2008 | 2014 | Change - 2008 to 2014 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area | Area | Area | ||||

| Ha | Percent | Ha | Percent | Ha | Percent | |

| Crop and Pasture | 2410 | 47 | 2390 | 47 | -20 | |

| Wetland | 1021 | 20 | 1033 | 21 | 12 | 1 |

| >Evaluated | (551) | (11) | (551) | (11) | (0) | (0) |

| >Unevaluated | (470) | (9) | (482) | (10) | (12) | (1) |

| Woodland | 949 | 19 | 937 | 18 | -12 | -1 |

| Settlement | 294 | 6 | 317 | 6 | 23 | |

| Meadow-Thicket | 220 | 4 | 217 | 4 | -3 | |

| Transportation | 123 | 2 | 123 | 2 | ||

| Water | 78 | 2 | 78 | 2 | ||

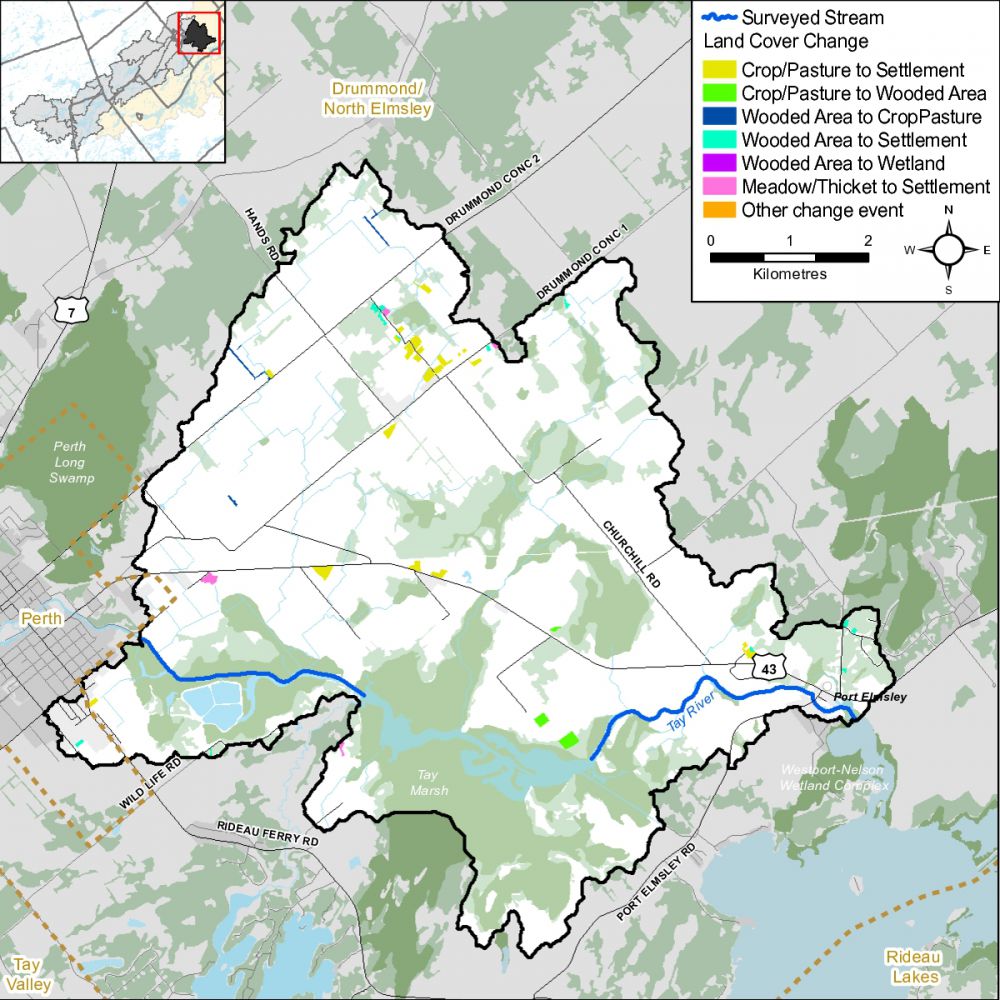

From 2008 to 2014, there was an overall change of 30 hectares (from one land cover class to another). Most of the change in the Port Elmsley catchment is a result of crop and pastureland being converted to settlement and reverting to woodland (Figure 48).

Table 8 provides a detailed breakdown of all land cover change that has taken place in the Port Elmsley catchment between 2008 and 2014.

| Land Cover | Change - 2008 to 2014 | |

|---|---|---|

| Area | ||

| Ha. | Percent | |

| Crop and Pasture to Settlement | 17 | 55.6 |

| Crop and Pasture to Woodland | 5 | 16.4 |

| Woodland to Settlement | 3.4 | 11.3 |

| Meadow-Thicket to Settlement | 3.2 | 10.3 |

| Woodland to Crop and Pasture | 2 | 6.4 |

4.2 Woodland Cover

In the Environment Canada Guideline (Third Edition) entitled “How Much Habitat Is Enough?” (hereafter referred to as the “Guideline”) the opening narrative under the Forest Habitat Guidelines section states that prior to European settlement, forest was the predominant habitat in the Mixedwood Plains ecozone. The remnants of this once vast forest now exist in a fragmented state in many areas (including the Rideau Valley watershed) with woodland patches of various sizes distributed across the settled landscape along with higher levels of forest cover associated with features such as the Frontenac Axis (within the on-Shield areas of the Rideau Lakes and Tay River subwatersheds). The forest legacy, in terms of the many types of wildlife species found, overall species richness, ecological functions provided and ecosystem complexity is still evident in the patches and regional forest matrices (found in the Tay River subwatershed and elsewhere in the Rideau Valley watershed). These ecological features are in addition to other influences which forests have on water quality and stream hydrology including reducing soil erosion, producing oxygen, storing carbon along with many other ecological services that are essential not only for wildlife but for human well-being.

The Guideline also notes that forests provide a great many habitat niches that are in turn occupied by a great diversity of plant and animal species. They provide food, water and shelter for these species - whether they are breeding and resident locally or using forest cover to help them move across the landscape. This diversity of species includes many that are considered to be species at risk. Furthermore, from a wildlife perspective, there is increasing evidence that the total forest cover in a given area is a major predictor of the persistence and size of bird populations, and it is possible or perhaps likely that this pattern extends to other flora and fauna groups. The overall effect of a decrease in forest cover on birds in fragmented landscapes is that certain species disappear and many of the remaining ones become rare, or fail to reproduce, while species adapted to more open and successional habitats, as well as those that are more tolerant to human-induced disturbances in general, are able to persist and in some cases thrive. Species with specialized-habitat requirements are most likely to be adversely affected. The overall pattern of distribution of forest cover, the shape, area and juxtaposition of remaining forest patches and the quality of forest cover also play major roles in determining how valuable forests will be to wildlife and people alike.

The current science generally supports minimum forest habitat requirements between 30 and 50 percent, with some limited evidence that the upper limit may be even higher, depending on the organism/species phenomenon under investigation or land-use/resource management planning regime being considered/used.

As shown in Figure 49, 20 percent of the Port Elmsley catchment contains 937 hectares of upland forest and 81 hectares of lowland forest (treed swamps) versus the 47 percent of woodland cover in the Tay River subwatershed. This is greater than the 30 percent of forest cover that is identified as the minimum threshold required to sustain forest birds according to the Guideline and which may only support less than one half of potential species richness and marginally healthy aquatic systems. When forest cover drops below 30 percent, forest birds tend to disappear as breeders across the landscape.

4.2.1 Woodland (Patch) Size

According to the Ministry of Natural Resources’ Natural Heritage Reference Manual (Second Edition), larger woodlands are more likely to contain a greater diversity of plant and animal species and communities than smaller woodlands and have a greater relative importance for mobile animal species such as forest birds.

Bigger forests often provide a different type of habitat. Many forest birds breed far more successfully in larger forests than they do in smaller woodlots and some rely heavily on forest interior conditions. Populations are often healthier in regions with more forest cover and where forest fragments are grouped closely together or connected by corridors of natural habitat. Small forests support small numbers of wildlife. Some species are “area-sensitive” and tend not to inhabit small woodlands, regardless of forest interior conditions. Fragmented habitat also isolates local populations, especially small mammals, amphibians and reptiles with limited mobility. This reduces the healthy mixing of genetic traits that helps populations survive over the long run (Conserving the Forest Interior. Ontario Extension Notes, 2000).

The Environment Canada Guideline also notes that for forest plants that do not disperse broadly or quickly, preservation of some relatively undisturbed large forest patches is needed to sustain them because of their restricted dispersal abilities and specialized habitat requirements and to ensure continued seed or propagation sources for restored or regenerating areas nearby.

The Natural Heritage Reference Manual continues by stating that a larger size also allows woodlands to support more resilient nutrient cycles and food webs and to be big enough to permit different and important successional stages to co-exist. Small, isolated woodlands are more susceptible to the effects of blowdown, drought, disease, insect infestations, and invasions by predators and non-indigenous plants. It is also known that the viability of woodland wildlife depends not only on the characteristics of the woodland in which they reside, but also on the characteristics of the surrounding landscape where the woodland is situated. Additionally, the percentage of forest cover in the surrounding landscape, the presence of ecological barriers such as roads, the ability of various species to cross the matrix surrounding the woodland and the proximity of adjacent habitats interact with woodland size in influencing the species assemblage within a woodland.

In the Port Elmsley catchment (in 2014), one hundred and one (48 percent) of the 209 woodland patches are very small, being less than one hectare in size. Another 94 (45 percent) of the woodland patches ranging from one to less than 20 hectares in size tend to be dominated by edge-tolerant bird species. The remaining 14 (seven percent of) woodland patches range between 22 and 129 hectares in size. Thirteen of these patches contain woodland between 20 and 100 hectares and may support a few area-sensitive species and some edge intolerant species, but will be dominated by edge tolerant species.

Conversely, one (less than one percent) of the 209 woodland patches in the drainage area exceed the 100 plus hectare size needed to support most forest dependent, area sensitive birds and are large enough to support approximately 60 percent of edge-intolerant species. No patch tops 200 hectares, which according to the Environment Canada Guideline will support 80 percent of edge-intolerant forest bird species (including most area sensitive species) that prefer interior forest habitat conditions.

Table 9 presents a comparison of woodland patch size in 2008 and 2014 along with any changes that have occurred over that time. A decrease (of one hectare) has been observed in the overall woodland patch area between the two reporting periods with most change occurring in the 20 to 50 woodland patch size class range. Seven new woodland patches have been created as a result of the forest loss/gain portrayed in Figure 49, some of which has resulted in an increase in forest fragmentation across the catchment.

| Woodland Patch Size Range (ha) | Woodland* Patches | Patch Change | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 2014 | 2008 to 2014 | ||||||||

| Number | Area | Number | Area | Number | Area | |||||

| Count | % | Ha | % | Count | % | Ha | % | Count | Ha | |

| Less than 1 | 96 | 48 | 44 | 4 | 101 | 48 | 45 | 4 | 5 | 1 |

| 1 to 20 | 92 | 45 | 439 | 43 | 94 | 45 | 440 | 43 | 2 | 1 |

| 20 to 50 | 12 | 6 | 355 | 35 | 12 | 6 | 352 | 35 | -3 | |

| 50 to 100 | 1 | <1 | 50 | 5 | 1 | <1 | 50 | 5 | ||

| 100 to 200 | 1 | <1 | 130 | 13 | 1 | <1 | 130 | 13 | ||

| Totals | 202 | 100 | 1018 | 100 | 209 | 100 | 1017 | 100 | 7 | -1 |

4.2.2 Woodland (Forest) Interior Habitat

The forest interior is habitat deep within woodlands. It is a sheltered, secluded environment away from the influence of forest edges and open habitats. Some people call it the “core” or the “heart” of a woodland. The presence of forest interior is a good sign of woodland health, and is directly related to the woodland’s size and shape. Large woodlands with round or square outlines have the greatest amount of forest interior. Small, narrow woodlands may have no forest interior conditions at all. Forest interior habitat is a remnant natural environment, reminiscent of the extensive, continuous forests of the past. This increasingly rare forest habitat is now a refuge for certain forest-dependent wildlife; they simply must have it to survive and thrive in a fragmented forest landscape (Conserving the Forest Interior. Ontario Extension Notes, 2000).

The Natural Heritage Reference Manual states that woodland interior habitat is usually defined as habitat more than 100 metres from the edge of the woodland and provides for relative seclusion from outside influences along with a moister, more sheltered and productive forest habitat for certain area sensitive species. Woodlands with interior habitat have centres that are more clearly buffered against the edge effects of agricultural activities or more harmful urban activities than those without.

In the Port Elmsley catchment (in 2014), the 209 woodland patches contain 20 forest interior patches (Figure 49) that occupy seven percent (656 ha.) of the catchment land area (which is greater than the five percent of interior forest in the Tay River Subwatershed). This is below the ten percent figure referred to in the Environment Canada Guideline that is considered to be the minimum threshold for supporting edge intolerant bird species and other forest dwelling species in the landscape.

Most patches (19) have less than 10 hectares of interior forest, 11 of which have small areas of interior forest habitat less than one hectare in size. The remaining patch contains 127 hectares of interior forest. Between 2008 and 2014, there has been no change in the number and area of woodland patches containing interior habitat (Table 10).

| Woodland Interior Habitat Size Range (ha) | Woodland Interior | Interior Change | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 2014 | 2008 to 2014 | ||||||||

| Number | Area | Number | Area | Number | Area | |||||

| Count | Percent | Ha | Percent | Count | Percent | Ha | Percent | Count | Ha | |

| Less than 1 | 12 | 60 | 3 | 6 | 11 | 55 | 3 | 4 | -1 | |

| 1 to 10 | 7 | 35 | 27 | 48 | 8 | 40 | 27 | 49 | 1 | |

| 10 to 30 | 1 | 5 | 26 | 46 | 1 | 5 | 26 | 47 | ||

| Totals | 20 | 100 | 56 | 100 | 20 | 100 | 56 | 100 | ||

4.3 Wetland Cover

Wetlands are habitats forming the interface between aquatic and terrestrial systems. They are among the most productive and biologically diverse habitats on the planet. By the 1980s, according to the Natural Heritage Reference Manual, 68 percent of the original wetlands south of the Precambrian Shield in Ontario had been lost through encroachment, land clearance, drainage and filling.

Wetlands perform a number of important ecological and hydrological functions and provide an array of social and economic benefits that society values. Maintaining wetland cover in a watershed provides many ecological, economic, hydrological and social benefits that are listed in the Reference Manual and which may include:

- contributing to the stabilization of shorelines and to the reduction of erosion damage through the mitigation of water flow and soil binding by plant roots

- mitigating surface water flow by storing water during periods of peak flow (such as spring snowmelt and heavy rainfall events) and releasing water during periods of low flow (this mitigation of water flow also contributes to a reduction of flood damage)

- contributing to an improved water quality through the trapping of sediments, the removal and/or retention of excess nutrients, the immobilization and/or degradation of contaminants and the removal of bacteria

- providing renewable harvesting of timber, fuel wood, fish, wildlife and wild rice

- contributing to a stable, long-term water supply in areas of groundwater recharge and discharge

- providing a high diversity of habitats that support a wide variety of plants and animals

- acting as “carbon sinks” making a significant contribution to carbon storage

- providing opportunities for recreation, education, research and tourism

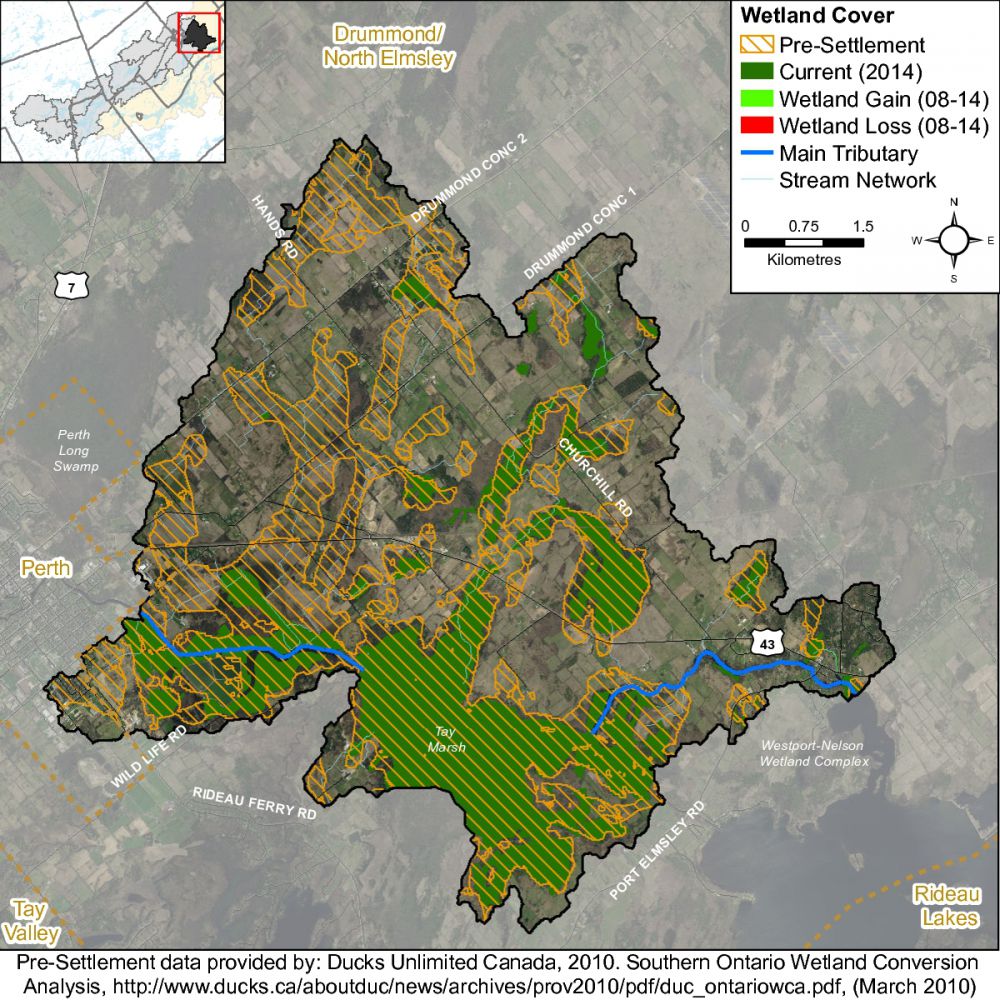

Historically, the overall wetland coverage within the Great Lakes basin exceeded 10 percent, but there was significant variability among watersheds and jurisdictions, as stated in the Environment Canada Guideline. In the Rideau Valley Watershed, it has been estimated that pre-settlement wetland cover averaged 35 percent using information provided by Ducks Unlimited Canada (2010) versus the 21 percent of wetland cover existing in 2014 derived from DRAPE imagery analysis.

This decline in wetland cover is also evident in the Port Elmsley catchment (as seen in Figure 50 and summarized in Table 11), where wetland was reported to cover 45 percent of the area prior to settlement, as compared to 20 percent in 2014. This represents a 55 percent loss of historic wetland cover. To maintain critical hydrological, ecological functions along with related recreational and economic benefits provided by these wetland habitats in the catchment, a “no net loss” of currently existing wetlands should be employed to ensure the continued provision of tangible benefits accruing from them to landowners and surrounding communities.

| Wetland Cover | Pre-settlement | 2008 | 2014 | Change - Historic to 2014 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area | Area | Area | Area | |||||

| Ha | Percent | Ha | Percent | Ha | Percent | Ha | Percent | |

| Port Elmsley | 2306 | 45 | 1021 | 20 | 1033 | 20 | -1285 | -55 |

| Tay River | n/a | n/a | 15280 | 19 | 15330 | 19 | n/a | n/a |

| Rideau Valley | 134115 | 35 | n/a | n/a | 82076 | 21 | -52039 | -39 |

4.4 Shoreline Cover

The riparian or shoreline zone is that special area where the land meets the water. Well-vegetated shorelines are critically important in protecting water quality and creating healthy aquatic habitats, lakes and rivers. Natural shorelines intercept sediments and contaminants that could impact water quality conditions and harm fish habitat in streams. Well established buffers protect the banks against erosion, improve habitat for fish by shading and cooling the water and provide protection for birds and other wildlife that feed and rear young near water. A recommended target (from the Environment Canada Guideline) is to maintain a minimum 30 metre wide vegetated buffer along at least 75 percent of the length of both sides of rivers, creeks and streams.

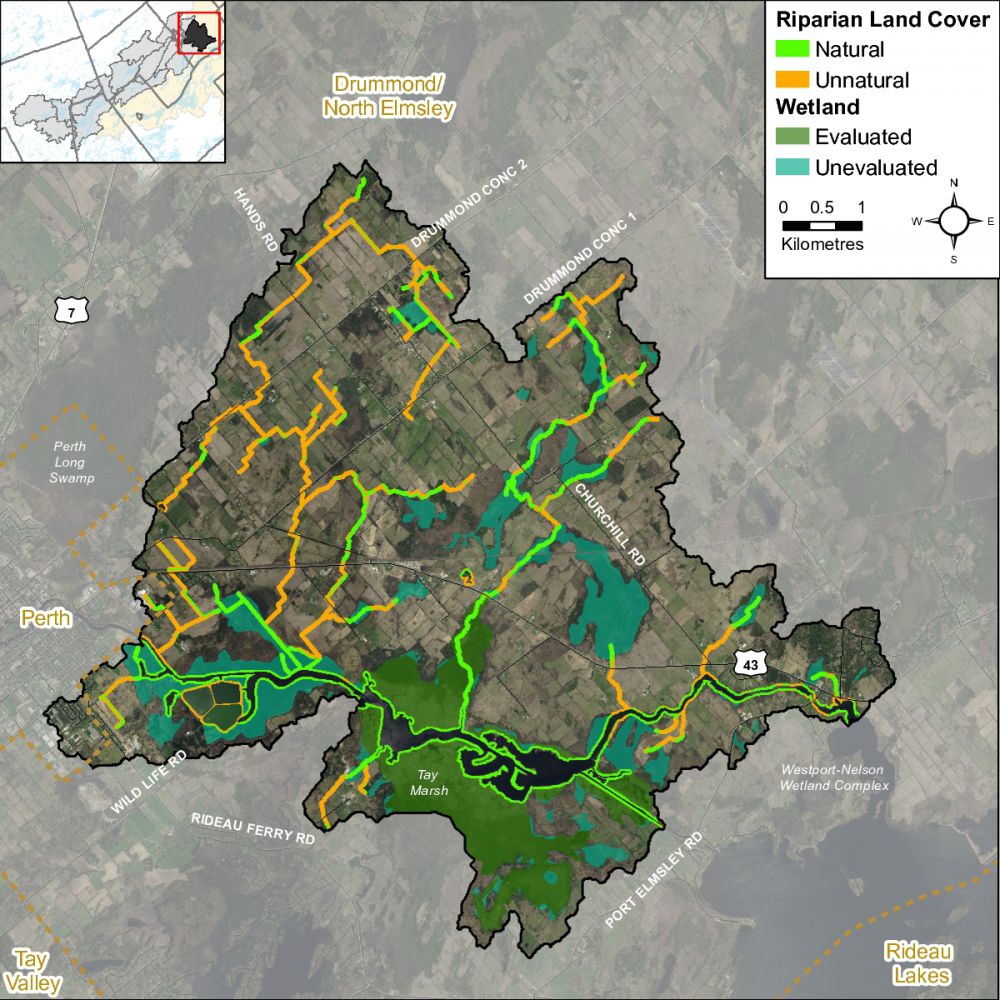

Figure 51 shows the extent of the ‘Natural’ vegetated riparian zone (predominantly wetland/woodland features) and ‘Other’ anthropogenic cover (crop/pastureland, roads/railways, settlements) along a 30-metre-wide area of land, both sides of the shoreline of the Tay River and its tributaries in the Port Elmsley catchment.

This analysis shows that the riparian zone in the Port Elmsley catchment is composed of crop and pastureland (42 percent), wetland (34 percent), woodland (14 percent), settlement (four percent), meadow-thicket (four percent) and transportation routes (two percent). Along the many watercourses (including headwater streams) flowing into the Tay River in the catchment, the riparian buffer is composed of crop and pastureland (55 percent), wetland (22 percent), woodland (14 percent), meadow-thicket (four percent), settlement areas (three percent) and transportation routes (two percent). Along the Tay River itself, the riparian zone is composed of wetland (72 percent), woodland (14 percent), crop and pastureland (six percent), meadow-thicket (four percent) and settlement (four percent).

Additional statistics for the Port Elmsley catchment are presented in Tables 12, 13 and 14 and show that there has been very little change in shoreline cover from 2008 to 2014.

| Riparian Land Cover | 2008 | 2014 | Change - 2008 to 2014 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area | Area | Area | ||||

| Ha. | Percent | Ha. | Percent | Ha. | Percent | |

| Crop and Pasture | 178.52 | 41.82 | 177.89 | 41.67 | -0.63 | -0.15 |

| Wetland | 146.86 | 34.41 | 147.50 | 34.55 | 0.64 | 0.14 |

| > Unevaluated | (86.50) | (20.27) | (87.14) | (20.41) | (0.64) | (0.14) |

| > Evaluated | (60.36) | (14.14) | (60.36) | (14.14) | (0.00) | (0.00) |

| Woodland | 59.52 | 13.94 | 58.63 | 13.73 | -0.89 | -0.21 |

| Settlement | 17.59 | 4.12 | 18.60 | 4.36 | 1.01 | 0.24 |

| Meadow-Thicket | 15.87 | 3.72 | 15.75 | 3.69 | -0.12 | -0.03 |

| Transportation | 8.49 | 1.99 | 8.49 | 1.99 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Riparian Land Cover | 2008.00 | 2014.00 | Change - 2008 to 2014 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area | Area | Area | ||||

| Ha. | Percent | Ha. | Percent | Ha. | Percent | |

| Wetland | 73.66 | 71.85 | 73.84 | 72.03 | 0.18 | 0.18 |

| > Unevaluated | (25.81) | (25.18) | (25.99) | (25.36) | (0.18) | (0.18) |

| > Evaluated | (47.85) | (46.67) | (47.85) | (46.67) | (0.00) | (0.00) |

| Woodland | 14.57 | 14.21 | 14.38 | 14.03 | -0.19 | -0.18 |

| Crop and Pasture | 6.18 | 6.04 | 6.18 | 6.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Meadow-Thicket | 3.98 | 3.89 | 3.98 | 3.89 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Settlement | 3.78 | 3.69 | 3.78 | 3.69 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Transportation | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Riparian Land Cover | 2008 | 2014 | Change - 2008 to 2014 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area | Area | Area | ||||

| Ha. | Percent | Ha. | Percent | Ha. | Percent | |

| Crop & Pasture | 170.33 | 54.79 | 169.7 | 54.59 | -0.63 | -0.20 |

| Wetland | 69.54 | 22.37 | 70 | 22.52 | 0.46 | 0.15 |

| > Unevaluated | (56.86) | (18.29) | (57.31) | (18.44) | (0.45) | (0.15) |

| >Evaluated | (12.68) | (4.08) | (12.69) | (4.08) | (0.01) | (0.00) |

| Woodland | 43.25 | 13.91 | 42.54 | 13.69 | -0.71 | -0.22 |

| Meadow-Thicket | 11.68 | 3.76 | 11.56 | 3.72 | -0.12 | -0.04 |

| Settlement | 8.30 | 2.67 | 9.31 | 3.00 | 1.01 | 0.33 |

| Transportation | 7.74 | 2.49 | 7.74 | 2.49 | 0.00 | 0.00 |